Lake Sakakawea & Knife River Indian Villages

Lake Sakakawea and Garrison Dam

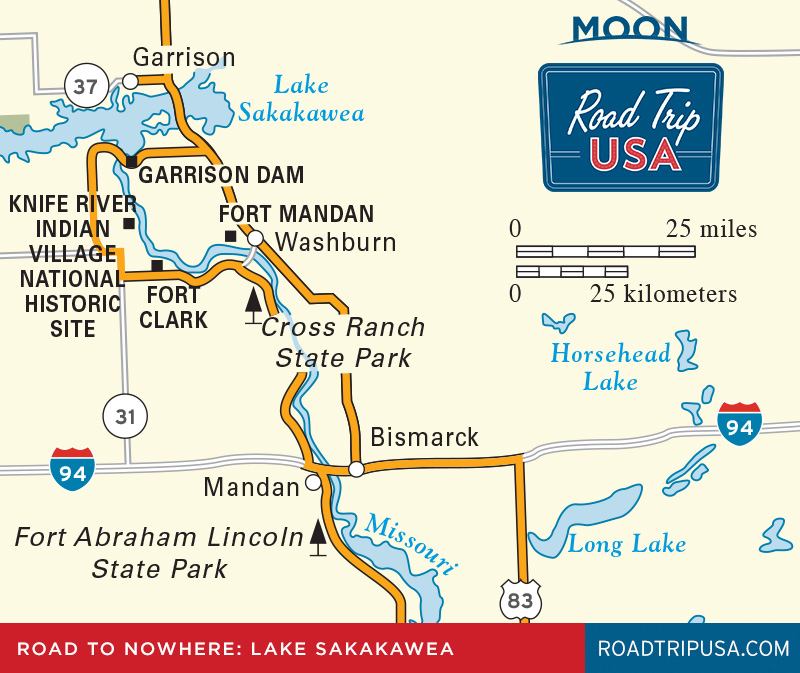

At 180 mi (290 km) long and with nearly 1,500 mi of shoreline along the dammed Missouri River, Lake Sakakawea is the third largest artificial “lake” in the United States. It’s one of many places in the northwestern United States named for the Shoshone woman, also known as Sacagawea, who accompanied the Lewis and Clark expedition across the Rocky Mountains. There are countless things to do on the water, most of them involving fishing. The pleasant town of Garrison (pop. 1,505), 6 mi (9.6 km) west of US-83 on Hwy-37, has a photogenic, 26-foot fiberglass statue of Wally Walleye.

At the south end of Lake Sakakawea, 12 mi (19.3) west of US-83 via Hwy-200, the Missouri River backs up behind wide but low-slung Garrison Dam, the fifth largest earth-filled dam in the United States. The powerhouse is enmeshed within a labyrinth of huge power stanchions, high-voltage lines, and transformers. In the adjacent fish hatchery on the downstream side of the dam, tanks hold hundreds of thousands of walleyes, pallid sturgeons, and northern pike, plus rainbow and brown trout.

South of Garrison Dam, roadside interest along US-83 focuses on leviathan testimonials to engineering prowess. Huge tractors and bulldozers raise clouds of dust at the extensive coal mining operations around Underwood. The whole area on both sides of US 83 has been strip-mined and restored, though current operations are hard to get a good look at. Some 7.5-8 million tons of the valuable black rock each year ends up at the 1,130-megawatt Coal Creek Station, 6 mi (9.6 km) north of Washburn and 2 mi (3.2 km) off the roadway but readily apparent. This is one of the largest lignite-fired coal plants in the country.

However, unless you have an abiding interest in fossil fuels, a more interesting alternative to driving this stretch of US-83 is to follow the Missouri River’s western bank south of Lake Sakakawea, where it reverts to its naturally broad and powerful self for the next 75 miles.

Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site

Between Garrison Dam and Washburn, scenic Hwy-200 passes two of North Dakota’s most significant historic sites: Fort Clark and the Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site (701/745-3300, daily, free), both of which, though small, saw key scenes of the late-18th and early-19th-century interactions between Native Americans and interloping European traders and explorers. Downstream from Garrison Dam along the west bank of the Missouri River, the Knife River Indian Villages is one of North Dakota’s most fascinating historic places, and the only federally maintained site devoted to preservation of the Plains nations’ cultures. Standing above the Missouri floodplain, on the site of what was the largest and most sophisticated village of the interrelated Hidatsa, Mandan, and Arikara peoples, the park protects the remains of dozens of terraced fields, fortifications, and earth lodges, remnants of a culture that lived here for thousands of years until the 1830s, when the communities were devastated by smallpox and other diseases introduced by European contact.

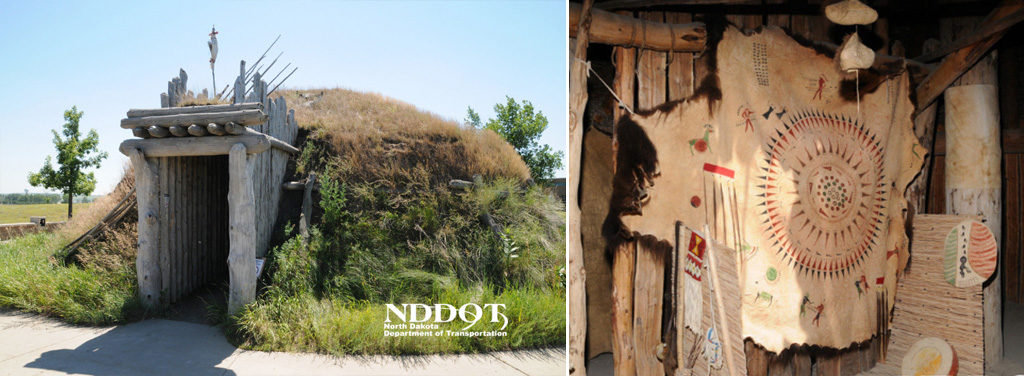

A highlight of the park is The Earthlodge, reconstructed using traditional materials, which gives a vivid sense of day-to-day Great Plains life. Measuring 42 ft (12.8 m) across and 15 ft (4.6 m) high at its central smoke hole, the earth lodge looks exactly as it would have when the likes of George Catlin and Karl Bodmer were welcomed by the villagers during the 1830s. Just north of the earth lodge, circular depressions spread in the soil—all that remain of the Hidatsa community where, in 1804, the Lewis and Clark Corps of Discovery was joined by the French fur-trapper Charbonneau and his wife, Sacagawea.

The modern visitors center, well signed off Hwy-200 at the south edge of the park, has archaeological and anthropological summaries that help bring to life these intriguing Native American peoples.

Fort Clark State Historic Site

Downstream 7 mi (11.3 km) and another 10 mi (16.1 km) by road from the Knife River site off Hwy-200, Fort Clark State Historic Site (701/328-3508, daily May-Sept., free) is as eerily isolated as can be. One of three major fur-trading posts on the upper Missouri River, Fort Clark was founded by the American Fur Company circa 1831, primarily to trade with the Mandan people. The fort was visited by other Native Americans, as well as the usual list of adventurers, explorers, and frontier luminaries, such as Prince Maximilian, George Catlin, and Karl Bodmer; unfortunately, the steamboats that plied the waters to bring supplies also brought smallpox, and in one tragic winter in 1837, the Mandan people’s population was cut by 90 percent. After the fur trade declined, Fort Clark was abandoned in 1860.

Today the tranquil site, approached on a narrow gravel-and-dirt road, is devoid of anything—it’s a somber, quiet piece of history stretching out on a grassy flat-topped bluff overlooking the Missouri River. Unfortunately, the silence and emptiness of the place are marred by the presence of a smoky Basin Electric Power Company coal plant up the river. A walking trail has markers designating the locations of eight original buildings, and depressions from an earth lodge village and primitive fortifications are still apparent, but you need to use your imagination to see much.